No matter your use for Linux, be it CentOS or Ubuntu, you will need to manage applications and services. I will cover the ways you can manage your software on a CentOS system, the next article will cover similar management on an Ubuntu system.

A lot of information will be covered in this article, so be sure you understand how it all works individually and together.

YUM and RPM

To start, let’s look at two commands which should be commonly used on any Red Hat system: YUM and RPM.

YUM stands for ‘Yellowdog Updater, Modified’ while RPM stands for ‘Red Hat Package Manager’. The two commands are the main tools we will use to manage most of the software on our CentOS systems.

YUM may be more familiar to anyone who has used a Red Hat Operating System (OS).

The simplest way to start with YUM is to install a software package. Let’s try something that most systems may not have installed, NMAP. The command to install NMAP is ‘sudo yum install nmap’. YUM needs to have ROOT permissions to be able to install software. You could use ‘sudo su’ to have a Root prompt and then you won’t need the ‘sudo’ command. When prompted to perform the installation, enter ‘y’ to proceed with the installation.

The YUM command uses the sub-command ‘install’ to have YUM install an application. In the case of the above command, the package being installed is ‘nmap’.

NOTE: For more information on NMAP, look at the article: NMAP TCP/IP Overview, NMAP Command Scans Part One, Part Two, Idle Scans, FTP Bounce Attack, Parameters, Ping Command, OS Detection and Services and Versions.

After NMAP has been installed, you can list information about the package with the command ‘yum info nmap’. You can exchange ‘nmap’ with any other package name.

NOTE: Be aware that the ‘yum info <package-name>’ command can be used on a package whether it is installed or not.

Software packages have what are call dependencies. When programmers write an application, it may require that you have another piece of software installed. The other piece of software is a dependency. Without the dependency, the software application will not run properly or at all. When a package is installed, it will install the required dependencies as well. If you want to see a list of dependencies then use the command ‘yum deplist <package-name>’. For example, you can see the dependencies for ‘nmap’ with the command ‘yum deplist nmap’. Again, the command can be run on a package that is or is not installed.

If a package is no longer needed, then use the command ‘yum remove <package-name>’. If you do not want ‘nmap’ then you can remove it with the command ‘yum remove nmap’.

If you want to see a list of all the packages installed on your system, then use the command ‘yum list installed’. Most of the packages should have been installed during the installation of the OS.

The list of available packages is downloaded from the repositories. Sometimes, the repositories are referred to as ‘repos’. The repos contain a very large list of packages that you do not have installed. To see the list of packages not installed on your system, you can use the command ‘yum list available’.

Now, let’s look at the RPM command. To see all the installed packages (software) on your system, use the command ‘rpm -qa’ in a Terminal. Keep in mind that these are not just the software packages you installed manually. The list includes any packages installed during the OS installation.

For only installed packages, use the command ‘rpm -qa’.

To see specific information on a package, you use the command ‘rpm -qi <package name>’.

If you want to see a list of files to be installed for a package, then use the command ‘rpm -ql <package-name>’. In this case, the command only works for those applications which have been installed.

The following two parameters used for RPM are special. The parameters are ‘-qpi’, which lists information on the package. The second parameter is ‘-qpl’ which lists the files in the package. Both of these parameters, used with RPM, can only be used with the downloaded package. To download a package, you use the ‘yum install <package-name>’ to prepare the install. When you are prompted to install if, there are three possible answers to the prompt. You can press ‘y’ to perform the installation. To cancel the installation, choose ‘n’. To download the file into cache, press ‘d’. Once the necessary files are downloaded, you can issue the command, pointing to the downloaded ‘rpm’ file. The YUM Cache is located at ‘var/cache/yum’. Search within this folder to find the files which were previously downloaded.

If you want to make an image of the system you are using for production, then clear the YUM Cache to clear space. The command is ‘yum clear all’.

Let’s say there is a file on your system and you don’t know which package it came from. For instance, the folder ‘/etc/plymouth’. You can use the command ‘rpm -qf /etc/plymouth’. The response I received was ‘plymouth-0.8.9-0.33.20140113.el7.centos.x86_64’. If I wanted to verify that the package was installed correctly, you can use the command ‘rpm -V plymouth-0.8.9-0.33.20140113.el7.centos.x86_64’. You should get no message, just a new line with a prompt waiting for input. In this case, the package is installed correctly.

Repositories

We hit on the topic of repositories above, but now we can cover managing it.

There is a list of repositories on your system that are used to check for system and software updates. When you perform an update or install, the system will first get the newest list of files from the repos. From the downloaded list, the installed package list is compared against the list to determine which packages have a newer version. When performing the upgrade, the system will then download and install any packages that have a newer version. The upgrade will, of course, include any needed dependencies. If a dependency is no longer needed by an updated package, then the dependency will be removed.

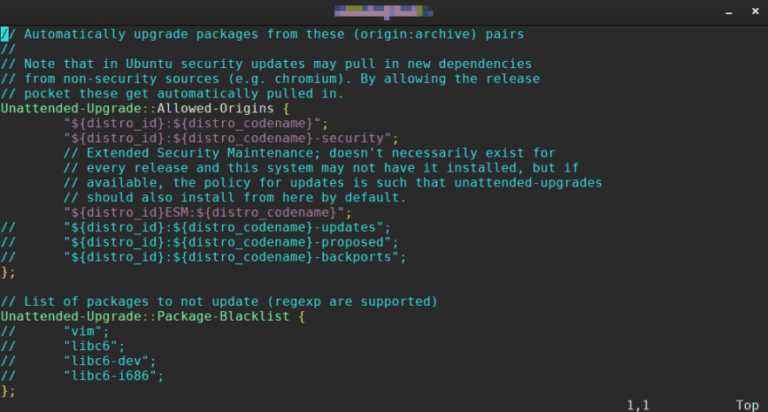

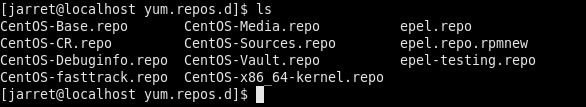

The repository information is saved in ‘/etc/yum.repos.d/’. You can see the results of my Repositories shown in Figure 01.

FIGURE 01

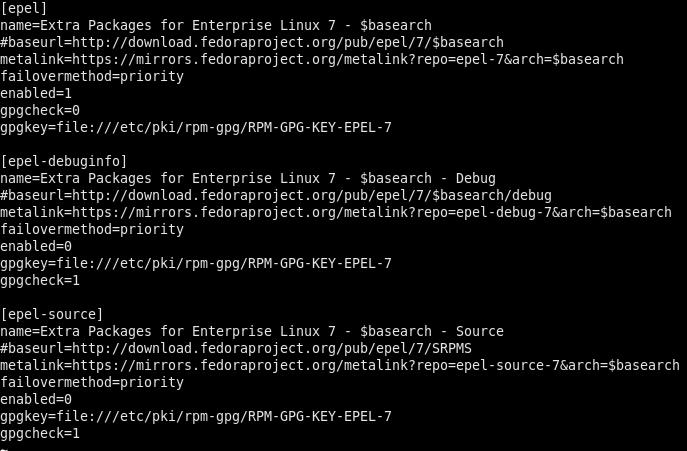

To see information on the repository, you can list the contents of a repo file. In Figure 2, you can see the contents of ‘epel.repo’.

FIGURE 02

One of the first main items is ‘baseurl’. The listing is the website address containing the files for the repository. A little down from that line is the ‘enabled=1’ line which shows that the repo is enabled for use. Just below that is the ‘gpgcheck=0’ line to specify that a signature is performed after download. In this case, the signature check is disabled.

To see that some repositories are disabled, you can list all available repositories with the command ‘yum repolist all’. The list will include enabled and disabled repos. The enabled repos will also list the number of packages available from the repository.

You can create your own repository list for specific software. Let’s say you work in a company. The company has proprietary software that is installed on each computer. A web server or file server could host the software for installation to each system. A repository file could be made which would allow each system to perform an update check. When the company updates the software, it could be placed on the appropriate server. Simply use a repository file to include your new server source. For a web server, use ‘http://’ source on the ‘baseurl’. On a File Server, use ‘file://’ instead.

The initial installation of the software would be done manually after the repo file is added.

Lets’ also say that the company may have a specific package they use company-wide. It has been found that an add-on only works with a specific version. You need to make sure that the systems in the company do not upgrade the software to a new version.

To prevent future upgrades of a package, you need to edit the file ‘yum.conf’ file in the folder ‘/etc/’. At the end of the file, just add ‘exclude=package*’, where ‘package’ is the name of the package you install from your local server or a repository. Save the file and you are done.

Cache

Yum creates a cache for the repos in the folder ‘/var/cache/yum’. The metadata files are stored in this location and used when performing package updates. Keep in mind that the contents are not the RPM files of the packages. The files are only the package lists.

If you want to update the package lists from repos, use the command ‘yum makecache’.

At this point, all the metadata files should be located in the folders. You can perform a listing of the contents more easily with the ‘tree’ command. At the end of the listing will be a count for the folders and files. Keep a mental note of this. To clear out the metadata, use the command ‘yum clean all’. Now, do a ‘tree’ of the ‘/var/yum/cache’ folder to see what is left. You should see that the folder count remains the same, but the file count is reduced drastically.

Be aware that the cache can be cleared and when an update is performed, the cache will be downloaded to perform a version check of the packages.

Installing from Source Code

There may be times that you can only get a package as source code. Other times, you may need to download the source code, make changes and re-compile it.

The quickest way to download source files is with a program called ‘yumdownloader’. To install the program, use the command ‘yum install yum-utils’. You need Root privileges to install the package.

Be aware that when downloading source code files, the file will be placed into your present working directory (pwd). If you are downloading a source file, you may want to create a special folder for it and change into that directory.

Let’s download an example file. I went to my home folder (cd ~) and created a folder named ‘htop’ (mkdir htop). I downloaded the source code file with the command ‘yumdownloader –source htop’.

By running a list command, ‘ls’, you can see there is a file in the new folder. Mine is named ‘htop-2.2.0-3.el7.src.rpm’. Yours file name may differ if the version has changed.

You can extract the file with the command ‘rpm2cpio htop-2.2.0-3.el7.src.rpm | cpio -idmv’. Change the file name if needed for your file. Now, the RPM file is extracted. Within the new files is a compressed file called ‘htop-2.2.0.tar.gz’. The extension of ‘gz’ shows it is a compressed file. Extracting the ‘gz’ file uses the command ‘tar -xvf htop-2.2.0.tar.gz’ If the file ended with the extension ‘bz2’, the parameter for ‘tar’ would be ‘-xjf’. The files should extract to another folder called ‘htop-2.2.0’. Change into the folder with the command ‘cd htop-2.2.0’.

In the new folder, you will find all of the necessary files containing the source code. To compile it, perform the following steps:

./configure

make

make install

The first line will validate that you have all the required dependencies installed for the package. The second line will compile the C code. The last line will install the newly compiled code.

To run the htop program, type the command ‘./htop’ to run it from the local folder.

If you use the command ‘whereis htop’, it should be listed as being in the folder ‘/usr/local/bin/’.

Conclusion

You should hopefully have been able to understand everything covered in the article. There was a lot of information to cover.

I will post another article on performing these steps on an Ubuntu system.